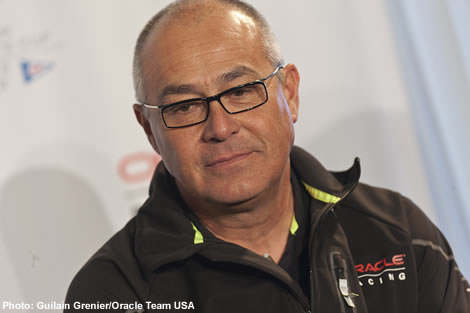

Dirk Kramers on foiling and AC72 design

Should we be surprised that the AC72s are fully foiling? On the one hand no – the logical conclusion of the lifting foils fitted to the ORMA 60s to the MOD70s and on Oracle’s 33rd America’s Cup winning trimaran USA 17, is getting the leeward hull consistently clear of the water. But on the other hand the writers of the AC72 rule took some steps (but clearly not enough) to try and make sure that the new breed of America’s Cup catamarans wouldn’t fly.

As a result the AC72s are in the difficult situation of foiling, only not terribly well.

“There are a number of features in the Rule that discourage flying, but clearly that didn’t quite work,” muses leading America’s Cup engineer Dirk Kramers, now part of Oracle Team USA’s Design Executive. “This is the trouble with rules always. Now we are flying and we are flying in a very difficult way and probably in a more expensive way than if there had been no rule.”

Under the AC72 rule daggerboards are allowed to be moved pretty much how you like – in addition to being dropped or raised they can be canted, their pitch altered, etc. However the rule states the windward board is not allowed to contribute to righting moment, trim tabs and moveable winglets are prohibited and the boards cannot protrude outboard beyond BMax. There is no such flexibility for the rudder - it can only rotate about a single axis up to 10° off vertical and again, trim tabs or moveable winglets are verboten.

“Pretty much as soon as the rule was issued it became apparent that things were available in the appendage part of the rule, that quite a lot was possible there,” continues Kramers. “It was obvious then that getting some degree of lift was going to be a pretty big aspect of it all. Then you just keep trying more and more and see if you can control it and so on. And it seems that at least three teams are fully flying with their boats.” He refers to all except Artemis Racing, which after the catastrophic destruction of its wing while training in Valencia, followed by a move to San Francisco is believed to be getting back in action imminently.

“It is not that difficult to fly,” Kramers continues. “It really all depends on how big a wing you put on the board. If you try to fly too early it is not going to be very fast. It is just about flying in a controlled way and in a controlled way that is fast. That is the challenge.”

Ideally if the teams were given carte blanche to go foiling they would want to be able either to alter the pitch of their T-foil rudders (a la Moth/International 14) or, more likely, fit a trim tab on the trailing edge of it, which would have a similar effect. They would also be looking to set up some sort of wave sensing mechanism, like a scaled-up equivalent of the wands used on a Moth, or the skis mounted ahead of the bows as used on the Hobie TriFoiler/Long Shot or perhaps even a very accurate accelerometer monitoring the pitching moment of the boat could be used in a similar manner.

This data, either mechanical or electronic, could then automatically adjust the amount of vertical lift the leeward daggerboard generates. Again this would ideally be carried out via a trim tab on the back of board (requiring substantially less power to drive it than attempting to alter the pitch of the entire board) although quite how even this would operate given that hydraulics are too slow and even a substantial push rod is probably not man enough is a challenge the design teams would have to take on.

Kramers continues: “You start tinkering around with smaller boats you try to see how you can control it, because if there were no rules it would be fairly easy to achieve with wands and things like the Moths use, but wands are not allowed in this rule so it becomes more difficult to fly in a stable way. We have to use things which are more difficult to achieve the same thing. That is where a lot of effort is going into trying to fly.”

While Alinghi 5 nearly did a reverse capsize, or a ‘wheelie’ at least, while training in Italy on one occasion – that scared the living daylights out of the crew at the time - such things are becoming a daily occurrence with the 72s when the breeze is up.

However while an airborne AC72 is one of the coolest sights presently in yachting – L’Hydroptere DCNS has been showponying around San Francisco Bay at speeds above 40 knots for the last few weeks showing how it’s done properly (without the constraints of an AC72 rule) – Kramers warns that there is a big difference between flying and flying fast. “It is not a guarantee it’ll be faster when you’re flying and there will be crossovers when flying is faster and sailing classically is faster and everyone is trying to figure out what that is.”

At present the AC72s we have seen foiling are only doing so off the breeze, but one imagines it is only a matter of time before they can do this upwind as well. Basically this comes down to the speeds the AC72s can achieve upwind, which one imagines will be in the 23-25 knot region and whether the size/section of the foils a team is using at this point are large enough to generate the required lift.

The biggest issue with designing the daggerboard/foils is attempting to make them versatile enough so they can prevent provide vertical lift in a rather broad range of boat speeds (say 15 to 45 knots) while also being able to prevent leeway upwind. Hence why we have seen Emirates Team New Zealand’s S-shape boards (which decant the board as it is lowered) like the ones used on Alinghi 5 but with an extra hook at the bottom and the ability to cant boards so they are closer to the vertical upwind (as they do on L’Hydroptere DCNS). And it is certain we have only caught a small glimpse of the board designs and operating mechanisms teams are working on for future iterations over the next few months.

“It is quite costly and time consuming to build foils. You need to play those cards quite carefully,” warns Kramers.

In addition to this there will obviously be a cut-off point in terms of wind speed/boat speed below which it won’t be worth trying to go foiling and where attempting to use lifting foils will simply create more drag than lift and be slower.

The Protocol for the 34th AC limits teams to building five pairs of daggerboards and it also appears that during the competition they can change their daggerboards daily to suit the anticipated conditions, although each time this would require them going through the procedure of obtaining a new measurement certificate.

Kramers points out making a call on which boards to use will be a difficult one. “When you start races in San Francisco, the wind builds quite quickly.”

When it comes to the wingsail Kramers points out that its main dimensions are well defined in the AC72 rule. “The biggest differences are in proportions of flap to main element size and then the style of foil section. You can choose to go with a relatively thin foil section which will give you some opportunities in some areas, but that might be heavy and if you think that is worth the weight to take those advantages you end up with one configuration. It seems that Team New Zealand and ourselves have gone for a fairly mainstream foil section on our first wings, whereas Artemis’ first wing was a bit more of a departure. It was thin with a relatively small flap size. Both TNZ and ourselves have four span-wise flans, whereas I think Artemis had seven. ”

Weight is another issue with the wings, the rule stipulating a minimum weight for it of 1325kg with a centre of gravity no less than 16.25m above the wing’s base plane.

“You have got to choose where you spend your weight,” says Kramers. “You can spend a lot of weight on stiffness, on a more complex or sophisticated control system or whatever you want. You can even make your wing overweight, but that means that you have to take weight out of your platform.”

While design focus has been very much on the boards and the wingsails, little mention has been made of the hulls of the AC72. Kramers maintains that they are still extremely important representing one of the greatest sources of drag, although aerodrag on the rig is also a big deal once the boat is sailing at 40 knots. “Even the windage and the platform drag or the drag of the net – all these things take on different proportions when you start going upwind at speeds higher than 20 knots. Of all the boats I’ve been involved with these and the last two boats [USA17 and Alinghi 5] are the only ones where the VMG upwind is greater than the wind speed. I don’t think there are any other boats on the planet that will do that.”

Another new and significant issue with the design of the AC72s is how a short handed crew of 11 (compared to 16 on the V5 boats) will be able to get these ultra-quick and potentially very labour intensive racing machines around an impossibly tight race track within San Francisco Bay – in contrast, Kramers points out, to the 33rd America’s Cup where they raced on a giant course and perhaps tacked four times during the whole event.

“This is going to be very much more of a sailor event - the boat handling and course management and tactics and strategy is going to be a big big part of winning the race. Boat speed by itself isn’t going to do it, however your tactical options are a lot broader if you have a boat that is a little bit faster, and trying to figure out what boat handling compromises you can make to gain some straight line speed is probably the most difficult thing to assess.”

Or possibly what straight line speed compromises have to be made to ensure that the crew is able to turn corners efficiently.

“Here you are going to be tacking and gybing a lot, so the acceleration coming out of tacks and gybes is a big part of the analysis. A lot of energy is spent trying to analyse the whole acceleration and deceleration phase of the performance envelope.”

This is largely going to turn into a numbers game as the sailing team sort this out with the designers. As Kramers puts it: “It is better that you can have a boat that can be sailed at 90% 100% of the time rather than a boat that can be sailed at 100% 5% of the time. So that is sail handling and just ease of handling, not just in the mechanics of boat handling, but the behaviour. If you are slightly come out of a tack slightly under or slightly over, it is not going to ruin your tack completely. So the forgiveness in the turning your boat is an important feature.”

While latest generation multihulls tack considerably better than they once did, through better understanding of boat design, platform stiffness and the skill of the crew, they still don’t look very efficient tacking as they come to a virtual standstill going through the wind. However Kramers says that in terms of actual boat lengths lost in a tack there is not that big a different compared to a monohull.

“They accelerate a lot faster. We have analysed the complete metres lost in a tack, but at the moment there is still an enormous learning curve. The guys who know how to tack at 95% all the time are going to have a big advantage over the guys who are going to be at 100% of some of the time and 30% other parts of the time.”

From an engineering perspective, Kramer’s home territory, the AC72s represent a new challenge. “With the Version 5 boats after a while you get such a history of them that you know where you are going to be weight-wise. You are fine tuning where you are. Right now we are in a new territory, so it is difficult to hit it spot on. The key is that you need to make sure you have enough weight left over in the bank to deal with the inevitable repairs that are going to come up in the next year. The way the rule is written you want to be at the maximum weight that the rule allows that gives you the highest stability but you can’t be over, so if it is too much you are going to have to give up some of your features.

“Within the 5900kg there are many things you can do, and it is basically a case of choosing how you want to spend that weight – if you want to spend it on boat handling features, on aerodynamic gizmos, on wing control system or board control systems, etc. In our internal discussions we talk about spending weight that anyone else would be talking about spending money and on top of that you have money problem as well – so you have two bank accounts – and both of them are limited!”

In this early phase of the campaign in these leading edge new generation boats, breakage is also proving to be a significant issue – less the breakage themselves than the time it takes out of a campaign when they have no spare wing or spare boards. “That is the biggest lesson that we took from the Artemis misfortune [their wing breakage]. It really had a big impact on their campaign in terms of how their development program goes. We are seeing that now with our board failure - it can stop you from sailing quite easily and that derails your development program in terms of how and when you build all these parts.”

So ideally you want to break you boat later in the campaign.

These are fascinating times for designers in the America’s Cup and we wait with bated breath to see what else the teams have up their sleeves over the next months.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latest Comments

Add a comment - Members log in